Sociology

Modernity and Social Changes in Europe and Emergence of Sociology

Modernity refers to a distinct period in human history marked by a shift toward scientific reasoning, as opposed to metaphysical or supernatural beliefs.

It emphasizes individualism, industrialization, technological progress, and the rejection of certain traditional values.

In sociology, modernity describes the era characterized by significant scientific, technological, and socioeconomic transformations, which began in Europe around 1650 and continued until roughly 1950.

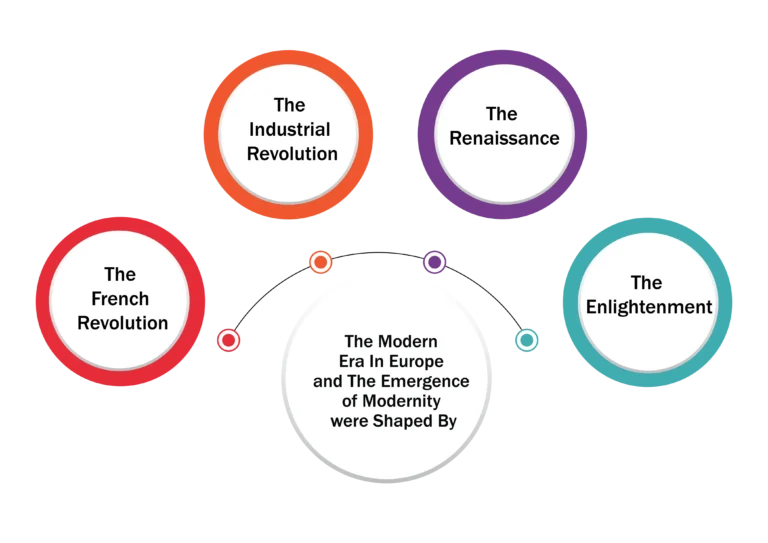

The modern era in Europe and the emergence of modernity were shaped by the following key events:

The Renaissance

- The Renaissance was a vibrant period of cultural, artistic, political, and economic revival in Europe, following the Middle Ages.

- Spanning roughly from the 14th to the 17th century, it fostered the rediscovery of classical philosophy, literature, and art.

- This era saw the flourishing of some of the most influential thinkers, writers, statesmen, scientists, and artists in history, while global exploration introduced Europe to new lands and cultures, expanding its commercial horizons.

- The Renaissance is widely recognized for bridging the Middle Ages and the modern world.

Changes during the Renaissance

- Visual Art- Art, literature, and science thrived, with a focus on studying nature and the human body scientifically. Paintings from this time often showcased detailed depictions of both.

- Medicine- Dissecting human bodies became acceptable, allowing doctors to study how the body was built. This led to major progress in anatomy, physiology, and pathology.

- Chemistry – A general theory of chemistry emerged, with studies focusing on chemical processes like oxidation, reduction, distillation, and amalgamation.

- Navigation and Astronomy- This period saw major exploration milestones, with Vasco da Gama reaching India in 1498 and Columbus discovering America in 1492. It was an era of expanding trade and early colonialism. Interest in astronomy also grew, as it played a crucial role in successful navigation.

- The Copernican Revolution – Nicholas Copernicus, a Dutchman, made the first significant break from ancient beliefs. At the time, people believed the Earth was fixed, with the sun and planets revolving around it (the “geocentric” theory). Copernicus challenged this by showing that the Earth actually moves around a fixed sun (the “heliocentric” theory).

Science during the Renaissance adopted a new approach to studying both man and nature. Natural objects were closely observed and experimented on. This period emphasized humanism, modern ideas, and encouraged intellectual growth, rationalism, empiricism, and a focus on change.

The Enlightenment

- The Enlightenment was an intellectual movement, primarily centred in France and Britain, lasting from the 1680s to 1789.

- This period was influenced by earlier writers and scientists like Galileo (Italian), Newton (English), Francis Bacon (English, 1561-1626), and René Descartes (French, 1596-1650), who explored the natural world and systems of thought.

- Key Enlightenment figures include Hobbes, Locke, Diderot, Montesquieu, and Rousseau, with the French writers known as the philosophes.

- These thinkers were often religious sceptics, political reformers, cultural critics, historians, and social theorists.

- Enlightenment writings had a profound impact on politics and the rise of sociology.

- Enlightenment ideas heavily influenced the political and social changes of the time. The revolutionary slogans “liberty, equality, fraternity” and “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” reflect the political ideals rooted in Enlightenment thought.

In the 18th century, Europe entered the Age of Reason and Rationalism, influenced by major philosophers like Montesquieu, Locke, Voltaire, Rousseau, Adam Smith, and John Stuart Mill.

- Montesquieu: In his book “The Spirit of the Laws”, he argued against concentrating power in one place and advocated for the “separation of powers” among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches to protect individual liberty.

- John Locke: This English philosopher believed every person has certain “inalienable rights”, including the right to life, property, and personal freedom. He argued that rulers who violate these rights should be removed and replaced by those who protect them.

- Voltaire: A French philosopher, Voltaire championed “religious tolerance” and “freedom of speech”, emphasizing individual rights and expression.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau: In “The Social Contract”, Rousseau stated that people have the right to choose their government. He believed individuals can best develop their personalities under a government of their own choosing.

- Mary Wollstonecraft: She was an English author and feminist, best known for her influential book, “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” (1792), embraced the idea of the “rational, self-determining individual”. She argued that women are not naturally different from men; rather, the differences arise from “socially constructed gender roles”. She believed that women, like men, are rational beings and deserve equal opportunities to develop their reasoning and moral skills.

This period marked a significant change in people’s thinking, leading society to adopt a more pragmatic approach

Changes during the Enlightenment in Europe:

- Promotion of Reason: Emphasized reason and scientific thinking over tradition and superstition.

- Human Rights: Advocated for individual rights and freedoms, influencing modern human rights movements.

- Political Change: Inspired revolutions, such as the American and French Revolutions, leading to the decline of monarchies and the rise of democratic governments.

- Secularism: Reduced the power of religious institutions and promoted secular governance.

- Social Reform: Encouraged social changes, including the abolition of slavery and the push for gender equality.

- Educational Expansion: Increased emphasis on education and literacy, leading to the establishment of public education systems.

- Cultural Development: Influenced art, literature, and philosophy, fostering a culture of critical thinking and debate.

- Scientific Advancements: Laid the groundwork for modern scientific inquiry and innovation.

These results significantly shaped modern European society and thought.

The French Revolution

- The French Revolution (1789-1799) was a period of profound social, political, and economic upheaval in France.

- It marked the end of absolute monarchy, the rise of republicanism, and the establishment of democratic ideals.

- Characterized by radical changes, the revolution sought to eliminate the inequalities of the feudal system and promote the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Causes of the French Revolution

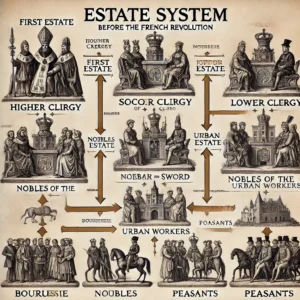

- Social Inequality: French society was divided into three estates:

- First Estate: Clergy, enjoying privileges and exemptions from taxes.

- Second Estate: Nobility, who held significant power and wealth.

- Third Estate: Common people, including peasants and the bourgeoisie, who bore the burden of taxation without political representation.

- Economic Hardship: France faced severe financial problems due to:

- Debt from wars, including involvement in the American Revolution.

- Poor harvests leading to food shortages and rising bread prices.

- High taxation on the Third Estate, leading to widespread discontent.

- Enlightenment Ideas: Enlightenment thinkers such as Rousseau, Voltaire, and Montesquieu promoted ideas of democracy, individual rights, and social contracts, challenging traditional authority and inspiring revolutionary thought.

- Weak Leadership: King Louis XVI’s indecisiveness and inability to resolve financial crises weakened the monarchy’s authority and credibility.

- Estates-General: The convening of the Estates-General in 1789 to address the financial crisis led to demands for more political representation, ultimately igniting revolutionary fervor.

Changes during the French Revolution

- End of Monarchy: The revolution led to the execution of King Louis XVI in 1793 and the establishment of the First French Republic.

- Rise of Radicalism: The revolution saw the emergence of radical factions, such as the Jacobins, and the Reign of Terror, during which thousands were executed, including political opponents.

- Social Changes: The feudal system was abolished, and various social reforms were implemented, including the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which emphasized individual rights and equality.

- Rise of Napoleon: The chaos following the revolution paved the way for Napoleon Bonaparte’s rise to power, leading to the establishment of the Napoleonic Empire.

- Influence on Other Revolutions: The French Revolution inspired other movements for change around the world, promoting ideas of democracy, nationalism, and human rights.

French Revolution was a pivotal event that reshaped France and had lasting impacts on the world, establishing principles that continue to influence modern democratic societies.

The Industrial Revolution

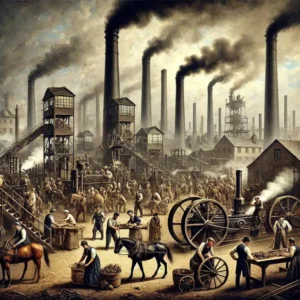

The Industrial Revolution began around 1760 AD in England and marked the foundation of modern industry. Spanning the late 18th and early 19th centuries, it brought significant material and social changes, primarily through the rise of industrialization and capitalism.

This period saw the birth of the factory system, which transformed production methods, led to the emergence of a middle class, and dismantled the feudal estates. While these developments resulted in various positive outcomes, such as increased productivity and economic growth, they also brought about numerous negative consequences.

In Europe, particularly in England, the discovery of new territories and the growth of trade and commerce led to an increased demand for goods. Previously, consumer items like cloth were produced through a domestic system, meaning they were made at home. However, with the rising demand, there was a need for large-scale production.

This shift brought significant changes to the social and economic lives of people, starting in England and eventually spreading to other European countries and later to other continents.

Changes during the Industrial Revolution:

- Labor Conditions: A new working class emerged, reliant on factory jobs, often living in poverty and harsh conditions. This social deprivation made them a significant social force.

- Recognition of Poverty: Sociologists identified the poverty faced by these workers as a result of social structures rather than being a natural condition, making the working class a focal point of moral and analytical concern in the 19th century.

- Property Transformation: Capital became crucial during the Industrial Revolution, with investments in the new industrial system gaining recognition. The influence of feudal landlords waned as new capitalists, many of whom were former landlords, rose to power.

- Urbanization: This period saw rapid urbanization, which was accompanied by increasing poverty and rising crime rates.

- Technological Advancements: Innovations in technology led to the development of the factory system.

- Social Condition Surveys: Increased interest in assessing social conditions through systematic surveys.

- Nuclear Family Emergence: The traditional family structure shifted towards the emergence of the nuclear family.

- Colonialism: The Industrial Revolution fuelled the expansion of colonialism as nations sought resources and markets for their industrial products.

Conservationist’s reaction to modernity

- The most extreme form of opposition to modernity was from French catholic counter-revolutionary philosophy as represented by the ideas of Louis de bonald and Joseph de Maistre.

- They saw these developments as disturbing characters to the peace and harmony of the society. They believed God had created society; people shouldn’t tamper with it and try to change the holy creation.

- Bonald opposed anything that undermined traditional institutions such as patriarchy, the Monarchy, the monogamous family and the Church. Believed religion as a useful and necessary component of social life.

- They saw French Revolution and Industrial revolution as disruptive forces. The conservatives tend to emphasize on old social order. Changes were seen as a threat not only to society and its components, but also to the individuals in it.

- They saw modern changes such as industrialization, urbanization and bureaucratization as causing disorganizing effects. These changes were viewed with fear and anxiety. Finally, conservatives supported the existence of a hierarchical system in the society.

Critical analysis of modernity

- Modernity is form of ideas, kind of perceptions and pattern of beliefs. Those who fall in love with modernity celebrate it; those people can’t adapt to changes feel as victim and criticize it.

- Modernity brings political unity and economic freedom. All philosophers and rational thinkers celebrated modernity for its achievements.

- Emile Durkheim stated that every society which changed from agrarian to industrial economy had its own problems. An anomie will be created in the society and it must be rectified by society itself.

- Karl Marx welcomes the change in society, but he accused that the fruits of modernity and its outcomes were enjoyed by one class and made other class to suffer.

- Augustus Comte, father of sociology believed in scientific study of social pattern, that is positivism. By using this positivism, he believed society can repair its problems.

- Max Weber also believed that, by using standard scientific methods, the scepticism of modernity can be cleaned out. Modernity is now a fully grown man. It can’t be turned as child. But we can cure the problems of society through the methods of sociology.

How these Social Changes led to emergence of Sociology?

- Modernity significantly affected the social, economic, and political lives of people. Initially viewed positively, its negative consequences soon became evident.

- Social Dislocation: Rapid urbanization led to the breakdown of traditional communities and social structures.

- Inequality: Economic changes resulted in stark disparities between different social classes, particularly between the wealthy elite and the working class.

- Environmental Degradation: Industrialization contributed to pollution, deforestation, and depletion of natural resources.

- Alienation: Individuals often felt disconnected from their work, society, and even themselves, as factory work became repetitive and dehumanizing.

- Consumerism: A focus on material goods fostered a culture of consumerism, leading to overconsumption and waste.

- Loss of Cultural Heritage: Traditional practices and values were often disregarded or lost in the pursuit of modernization and progress.

- Mental Health Issues: Increased stress and anxiety levels arose from rapid societal changes and the pressures of modern life.

- Political Instability: Modernity often led to upheaval, revolutions, and conflicts as groups struggled for power and rights.

- Exploitation of Labor: The emergence of factories often resulted in poor working conditions, long hours, and exploitation of workers, including children.

- Erosion of Community Bonds: A focus on individualism weakened communal ties and social solidarity, leading to isolation through Divorce and Breakups.

- These challenges posed by modernity spurred the development of new intellectual ideas.

- Existing disciplines were unable to address the emerging questions, leading to the creation of a new field known as sociology.

- Arising from its specific context, sociology was often referred to as the “science of the new industrial society.”

- While there was a general context for sociology’s emergence across Europe, France provided a unique socio-political backdrop, particularly influenced by the upheaval caused by the French Revolution.

- Intellectuals like Saint Simon, Auguste Comte, Herbert Spencer, and Émile Durkheim contributed foundational ideas to the discipline, seeking to understand the causes and consequences of these new societal changes.

- Simon initially referred to this field as social physics, while Comte was the first to coin the term sociology.

- Following Comte’s lead, Spencer introduced the concept of “social evolution,” akin to biological evolution.

- Durkheim’s efforts were instrumental in establishing sociology as the first academic department in France and Europe, solidifying its distinct status.

- This emerging discipline required a subject matter, data, perspectives, and methods. Influenced by the popularity of the natural sciences, sociology explored new scientific and rational methods.

- The “State of the Poor” report marked the first scientific survey in Europe, revealing that poverty is a social, rather than a natural, phenomenon.

The factual foundation for sociology was supported by existing historical records, while early theoretical perspectives were shaped by Comte, Spencer, and Durkheim. Hence Sociology emerged as a discipline to address the profound changes in the Society.

Previous Year Questions

- How had Enlightenment contributed to the emergence of Sociology? (2015)

- Discuss the historical antecedents of the emergence of Sociology as a discipline (2019)

- How did the intellectual forces lead to the emergence of Sociology? Discuss (2020)

- Europe was the first and the only place where modernity emerged. Comment (2021)

- What aspects of Enlightenment do you think paved way for the emergence of Sociology? Elaborate (2022)

- Sociology is the product of European Enlightenment and Renaissance. Critically examine this statement. (2024)

Important Keywords

Modernity, The Renaissance, The Enlightenment, The French Revolution, The Industrial Revolution, Urbanization, Emergence of Sociology, Saint Simon, Auguste Comte, Herbert Spencer, and Émile Durkheim, Social Changes, Monarchy, Vasco da Gama, Columbus, Louis de bonald, Joseph de Maistre and Individualism.

Scope of Sociology

- The term Sociology was coined by Auguste Comte, a French philosopher, in 1839.

- The teaching of sociology as a separate discipline started in 1876 in the United States, in 1889 in France, in 1907 in Great Britain, after World War I in Poland and India, in 1925 in Egypt and Mexico, and in 1947 in Sweden.

- Sociology is the youngest of all the Social Sciences.

- The word Sociology is derived from the Latin word ‘societies’ meaning ‘society’ and the Greek word ‘logos’ are meaning ‘study or science’.

- The etymological meaning of ‘sociology’ is thus the ‘science of society’.

- It can focus its analysis on interactions between teachers and students, between two friends or family members as well as it can also focus on national issues like unemployment, caste conflict, the effect of state policies on forest rights of the tribal population or rural indebtedness or examine global social processes such as:

- the impact of new flexible labor regulations on the working class;

- or that of the electronic media on the young or the entry of foreign universities on the education system of the country.

- What defines the discipline of sociology is not just what it studies (i.e. family or trade unions or villages) but how it studies a chosen field.

- There has been a great deal of controversy regarding the subject matter of sociology. Sociologists of different schools differ in their views.

Two Main Schools of Thought Regarding the Scope of Sociology

|

The Formalistic School

|

The Synthetic School

|

|---|---|

|

The Formalistic school wants to keep the scope of sociology distinct from other social sciences. |

The synthetic school wants to make sociology a synthesis of the social sciences or a general science. |

|

They regard sociology as pure and independent.

|

According to the synthetic school, the scope of sociology is encyclopedic and synoptic. |

Specialistic or Formalistic School

The name is so because sociology is a special science to study society.

George Simmel is the supporter.

Society has form and content – according to him and there can be no society without form and content and they can be separated i.e. form and content. He says sociology only studies the form but not the content.

- Competition – social studies the factor, result and this is the form the area of competition is the content and it is not studied.

Sociology does not study the content because there are other social sciences which study the contents.

- By him Tables 3 types of glass of similar forms fill them with different types of content but this does not change the form of the glass. Then now you take one glass and fill it by 3 different liquids one by one. Now the form does not change and the content too does not change and therefore these forms and contents can be separated.

Similarly, sociology studies the form and if there is a change in the content there is no change in the form and thus in the study.

Thinker’s view about Specialistic or Formalistic School

Simmel’s view

- According to Simmel, the distinction between Sociology and other special sciences is that it deals with the same topics as they from a different angle—from the angle of different modes of social relationships.

- Social relationships, such as competition, subordination, division of labour etc. are exemplified in different spheres of social life such as economic, the political and even the religious, moral or artistic but the business of Sociology is to disentangle these forms of social relationships and to study them in abstraction.

- Thus, according to Simmel, Sociology is a specific social science which describes, classifies, analyses and delineates the forms of social relationships.

Max Weber’s view

- Max Weber also makes out a definite field for Sociology.

- According to him, the aim of Sociology is to interpret or understand social behaviour.

- But social behaviour does not cover the whole field of human relations. Indeed, not all human inter-actions are social.

- For instance, a collision between two cyclists is in itself merely a natural phenomenon, but their efforts to avoid each other or the language they use after the event constitute true social behaviour.

- Sociology is thus, according to him, concerned with the analysis and classification of types of social relationships.

Von Wiese’s view

- According to Von Wiese, the scope of Sociology is the study of forms of social relationships.

- He has divided these social relationships into many kinds.

Vierkandt’s view

- He defined social as, Social is the study of the ultimate form of mental and psychic relationship which link one to another’.

- He gives important to emotional relationship.

Tonnie’s view

- He believes Sociology to be pure science. He said that Sociology is pure and independent.

- He divided society into two groups 1. Society and 2. Community.

- He said society is urban society whereas community is rural society and in Sociological terms he called it as Gescelschaft and Gescelschaft.

Criticism of Specialistic or Formalistic School

- Sociology is a science and it’s new in origin and so not a pure science.

- A. Sorokin says that it isn’t necessary to say it is a science and not correct to study scientifically.

- What is Society? There are difference aspects in society ans all these combined make society. These different social sciences are studied in different ways or by other social sciences. These social sciences are specialized in studying these aspects.

- George Simmel separated forms from content but this too is not correct. It may be correct in other sciences such as the physical sciences. If the form changes the content also changes. There is a difference in the ideas of the supporters of this group or school.

Synthetic school

The school of thought believes that sociology should study society as a whole and not confine itself to the study of only limited social problems.

The synthetic school wants to make sociology a synthesis of the social sciences or a general science, Durkheim, Hob-house and Sorokin subscribe to this view.

Thinker’s view about Synthetic school

Durkheim’s view

- “Sociology is a science of collective representation”. He believes in the collection of people in society.

- When there is collection there must be wider scope for collective representation there must be majority of people hence it will be social facts.

- Since it has a social fact, they are instrumental in guiding and controlling the behavior of society. (Those collective symbols accepted by the majority and what they say become social facts. These will help).

- These social facts will later become a part of society. When we study a collective representation the whole picture of society comes before us.

Sorokin’s view

- “Sociology is the generalizing science”. He is the profounder of systematic study.

- In his book ‘contemporary sociology’ he observes that social is a general science.

- It studies the general characteristics of the society of the relationship of social and non-social phenomena.

- He constructs a formula to describe his theory.

- Sociology- a, b, c

- Economics – a, b, c, d, e, f

- Political Science – a, b, c, g, h, i

- Religion – a, b, c, L, M, N

- Constitutional – a, b, c, n, y, Z A, b, c, are found in all social sciences.

Hobhouse’s view

- “Social is the synthesis of various social sciences”. He means social is a general study which studies society as a whole from all aspects i.e. the combination of all social sciences – Sociologist must pursue his study from a particular part of society (social friend).

- When he studies thus, he must interconnect his result with the results arrived from other social sciences and then he should interpret society as a whole.

Ginsberg’s view

- Ginsberg has summed up the chief functions of sociology as follows.

- Firstly, Sociology seeks to provide a classification of types and forms of social relationships especially of those which have come to be defined institutions and associations.

- Secondly, it tries to determine the relation between different parts of factors of social life, for example, the economic and political, the moral and the religious, the moral and the legal, the intellectual and the social elements.

- Thirdly, it endeavours to disentangle the fundamental conditions of social change and persistence and to discover sociological principles governing social life.

Thus, the scope of Sociology is very wide. It is a general science but it is also a special science. As a matter of fact, the subject matter of all social sciences is society. What distinguishes them from one another is their viewpoint.

Thus, economics studies society from an economic viewpoint; political science studies it from political viewpoint while history is a study of society from a historical point of view Sociology alone studies social relationships and society itself.

MacIver correctly remarks, what distinguishes each from each is the selective interest.

Green also remarks, “The focus of attention upon relationships makes Sociology a distinctive field, however closely allied to certain others it may be.”

Sociology studies all the various aspects of society such as social traditions, social processes, social morphology, social control, social pathology, effect of extra-social elements upon social relationships etc.

Actually, it is neither possible nor essential to delimit the scope of sociology because, this would be, as Sprott put it, “A brave attempt to confine an enormous mass of slippery material into a relatively simple system of pigeon holes.”

Changing nature of Scope of Sociology

The scope of sociology has evolved significantly from its origins in the 19th century, shaped by changing social realities.

Initially, sociology focused on understanding large-scale social structures, such as industrialization, capitalism, and social order.

Early thinkers like Auguste Comte and Émile Durkheim emphasized macro-level phenomena, seeking universal laws to explain societal stability and progress.

By the mid-20th century, sociology expanded its scope, influenced by structural functionalism and symbolic interactionism.

Talcott Parsons’ functionalism viewed society as a system of interdependent parts, while micro-level theories like symbolic interactionism explored everyday interactions and meaning-making.

The discipline also began to specialize, with subfields such as rural and urban sociology, demography, and education.

In the post-1960s era, sociology shifted towards critical perspectives, including Marxism, feminism, and critical race theory, emphasizing power, inequality, and social justice.

This period marked the study of race, gender, class, and sexuality, reflecting the rise of social movements.

The late 20th century brought globalization and postmodernism, challenging traditional boundaries and focusing on transnational phenomena, cultural identities, and global inequalities.

Sociology increasingly addressed global migration, environmental issues, and the impact of neoliberal capitalism.

In the 21st century, the digital revolution expanded the scope further, introducing digital sociology. This field explores how technology, social media, and algorithms shape human interaction, identity, and power structures.

Contemporary sociology is also more interdisciplinary, engaging with fields like environmental science and political economy, while emphasizing decolonization and the inclusion of non-Western perspectives.

Hence sociology’s scope has grown to include both macro- and micro-level analyses, integrating diverse, global, and digital phenomena that reflect the complexities of the modern world.

Previous Year Questions

- Sociology is pre-eminently study of modern societies. Discuss (2016)

- In the context of globalisation, has the scope of sociology been changing in India? Comment. (2020)

Important Keywords

Auguste Comte, Specialistic or Formalistic School, George Simmel, Max Weber, Von Wiese, P.A. Sorokin, Synthetic school, Durkheim, Hobhouse, Ginsberg, MacIver, Changing nature, Talcott Parsons, Rural and Urban sociology, Globalization and Postmodernism, Digital Sociology.

Sociology and Common Sense

Commonsense knowledge is the routine knowledge people have of their everyday world and activities.

The common-sense explanations are generally based on what may be called ‘naturalistic’ and/or individualistic explanation based on taken for granted knowledge.

Sociology has its tryst with common sense since long time and it has been accused of being no more than common sense right from its birth.

Example: “Women are more emotional than men”.

Thinkers’ view:

- Andre Beteille: Sociological knowledge tends to be general, if not universal, on the other hand commonsense knowledge is particular and localised.

- Durkheim: Sociology must break free of the prejudice of commonsense perceptions before it can produce scientific knowledge of the social world.

- Marxists: Most commonsense knowledge is ideological or at least very limited in its understanding of the world.

- Anthony Giddens: Sociological knowledge also becomes part of common-sense knowledge sometimes. For example – sociological research into marital breakdown has led people to believe that marriage is a risky proposition.

Relationship between Common Sense and Sociology

- Sociology draws a great deal from commonsense as the former touches the everyday experiences of lay persons. As a result, there is a tendency to use one in place of the other.

- Sociological knowledge tends to be general, if not universal, on the other hand commonsense knowledge is particular and localised.

- Commonsense is not only localised it is also unreflective since it does not question its own origin and presuppositions.

- Further, sociology also helps us to show that commonsense is highly variable.

- Sociology helps us to understand a society and this could be deepened and broadened by systematic comparison between one society with other whereas commonsense is not in a position to reach such an understanding. This becomes possible because sociology makes use of its tools and techniques for systematic investigation of the object while commonsense involves preconception, which is rejected by sociology.

- Commonsense easily constructs imaginary social arrangements which is utopian whereas sociology is anti-utopian in its central preoccupation with the disjunction between ideal and reality in human societies.

- Sociology is also anti-fatalistic in its orientation. It does not accept the particular constraints taken for granted by commonsense as eternal or immutable. It provides a clearer awareness than commonsense of the range of alternatives that have been or may be devised for the attainment of broadly the same ends.

- Sociology is further value neutral and free of all forms of biases and value judgements but commonsense is often a source of biases and errors.

- Commonsense knowledge is the routine knowledge people have of their everyday world and activities.

Different sociological approaches adopt different attitudes to commonsense knowledge.

- The Commonsense concept is central to Alfred Schutz’s phenomenological sociology, where it refers to organized and typified stocks of taken for granted knowledge upon which activities are based and that in the natural attitude are not questioned.

- For ethnomethodologists commonsense or tacit knowledge is a constant achievement in which people draw on implicit rules of how to carry on and which produce a sense of organisation and coherence.

- For symbolic interactionists and other interpretive sociologists there is a less rigorous analysis of commonsense knowledge, but the central aim of sociology is seen as explicating and elaborating people’s conceptions of the social world

- For Durkheim sociology must break free of the prejudice of commonsense perceptions before it can produce scientific knowledge of the social world.

- For Marxists much commonsense knowledge is ideological or at least very limited in its understanding of the world. Therefore, to begin with we should see the difference between knowledge derived from commonsense and those having origin in sociological research and systematic methods.

How Common-sense aids Sociology?

- Common sense aids sociologists in forming hypotheses: For instance, common sense might suggest that individuals from rural areas are more community-oriented. Sociologists can use this assumption to investigate social bonds in rural vs. urban settings, which can either validate or challenge the hypothesis.

- Common sense provides foundational ideas for sociological research: For example, the stereotype that people with higher education are less likely to commit crimes can be a starting point for research. Sociologists might explore crime rates in relation to education levels to test this belief.

- It also enriches sociology by questioning its findings: If common sense suggests that men are naturally better suited for leadership roles, but sociological research concludes that leadership is influenced more by socialization and opportunity than by gender, this contradiction can spur further investigation into gender roles and leadership.

- Hegel argues that philosophy evolves from everyday experience, making every individual a social theorist: A worker who perceives the wage gap as unfair might not have formal training in sociology but is, in a sense, theorizing about class inequality based on lived experiences—an insight sociology can later formalize and study.

- The relationship between common sense and sociology is fluid and can be mutually reinforcing: Common sense may lead to assumptions like “technology isolates people.” Sociological studies may either confirm this (showing increased loneliness with social media use) or challenge it (finding that technology enhances certain social connections), thus refining both sociological theory and common-sense beliefs.

Differences between Common sense and Sociology

|

Common sense

|

Sociology

|

|---|---|

|

Common sense generally takes cues from what appears on surface |

Sociology looks for inter-connections and root causes which may not be apparent |

|

Common sense uses conjectures and stereotypical beliefs

|

Sociology uses reason and logic

|

|

Common sense is based upon assumptions

|

Sociology is based upon evidences

|

|

Common sense is intuitive

|

Sociological knowledge is objective

|

|

Common sense promotes status-quo

|

Sociological knowledge is change oriented

|

|

Common sense based on personal judgements

|

Sociology is based on data, methods

|

|

Common sense knowledge may be very personal and two persons may draw different conclusion of a same event based on their own common sense |

Sociological knowledge results into generalization and even theory building |

|

Explanation of

|

Common Sense

|

Sociological

|

|---|---|---|

|

Poverty

|

People are poor because they are afraid of work, come from `problem families' are unable to budget properly, suffer from low intelligence and shiftlessness. |

Contemporary poverty is caused by the structure of inequality in class society and is experienced by those who suffer from chronic irregularity of work and low wages. |

Thus, a statement made on common sense basis may be just a guess, a hunch or a haphazard way of saying something generally based on ignorance, bias, prejudice or mistaken interpretation, though occasionally it may be wise, true, and a useful bit of knowledge.

At one-time, common-sense statements might have preserved folk wisdom but today, scientific method has become a common way of seeking truths about our social world.

Previous Year Questions

- Is Sociology common sense? Give reasons in support of your argument (2016)

- The focal point of Sociology rests on interaction. How do you distinguish it from common sense? (2018)

- How is Sociology related to common sense (2021)

- Do you think that common sense is the starting point of social research? What are its advantages & limitations? Explain (2023)

Important Keywords

Commonsense, Routine Knowledge, Sociology, Granted Knowledge, Andre Beteille, Durkheim, Anthony Giddens, Everyday Experiences, Localised, Unreflective, Anti-utopian, Anti-fatalistic, Value neutral, Phenomenological sociology, Ethnomethodologists, Symbolic interactionists, Hypothesis, Status-quo and Starting point of social research.

Sociology and Anthropology

Sociology

Sociology is the study of social life, exploring the social causes and effects of human behaviour.

As C. Wright Mills puts it, sociology seeks out the “public issues” that shape “private troubles.” Unlike common perceptions of human behaviour, sociology relies on systematic, scientific methods of inquiry and critically examines widely accepted beliefs about the social world.

Sociological thinking involves closely analysing society, often revealing that things are not as they initially appear.

For instance, a sociologist views unemployment not as an individual’s personal issue, but as a result of the interplay between economic, political, and social forces that influence job availability and access.

Anthropology

Anthropology is a comprehensive and holistic study of humanity, encompassing subfields such as archaeology, physical anthropology, cultural anthropology and linguistic anthropology.

Anthropologists examine human beings through a broad, comparative lens, exploring human experiences across different times and places, both past and present.

Cultural anthropologists focus on studying various cultures, including their own and those that are different, by immersing themselves in the culture to gain an insider’s perspective.

Social anthropology emerged in the West during a period when Western-trained anthropologists primarily studied non-European societies, which were often regarded as exotic, barbaric, or uncivilized.

This unequal dynamic between the observers and the observed was frequently noted in earlier times.

However, the situation has evolved, and today, former “natives”—whether Indian, Sudanese, Naga, or Santhal—now have the opportunity to speak and write about their own societies.

Differences between Sociology and Anthropology

|

Sociology

|

Anthropology

|

|---|---|

|

It deals with modern, civilized and complex societies.

|

It deals with primitive, uncivilised and simple societies.

|

|

It studies small as well as large societies.

|

It usually studies only small societies.

|

|

Sociologists use census, survey and questionnaire techniques.

|

Anthropologists use participant observation and ethno- methodology.

|

|

It gives importance in analysing the quantitative data.

|

It gives importance in analysing qualitative data.

|

|

Its scope is narrow as it studies social relationships.

|

Its scope is wide as it studies cultural and biological aspects.

|

|

The primary subfields of sociology consist of Social Organization, Sociological Social Psychology, Social Change, and Criminology. |

The main subfields of anthropology are Cultural Anthropology, Linguistic Anthropology, Biological/Physical Anthropology, and Archaeology. |

|

Important concepts in sociology encompass social structure, social function, conflict, social class, culture, and socialization. |

Important concepts in anthropology include culture, cultural relativism, ethnocentrism, cultural evolution, cultural adaptation, thick description, and ethnography. |

Similarities between Sociology and Anthropology

- Study of Human Societies and Behavior: Both anthropology and sociology examine how societies are formed, function, and evolve over time. They analyze how individuals and groups interact within these societies, considering the effects of these interactions on human relationships, societal dynamics, and social change. Both fields also explore societal roles, statuses, and shared behaviors, assessing their impact on human relations and social development.

- Use of Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: Both disciplines employ a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods. Qualitative approaches, such as in-depth observations, interviews, and document analysis, offer deep insights into human and social behavior. Meanwhile, quantitative methods, including surveys and statistical analyses, provide measurements of broader social phenomena and patterns of behavior.

- Analysis of Culture and Social Structures: Both anthropology and sociology extensively investigate culture, focusing on customs, rituals, norms, and the social orders that guide societies. They study how cultural factors influence, and are influenced by, societal structures and systems, paying particular attention to power dynamics, role differentiation, and the evolution of social institutions. These disciplines seek to understand how culture and social structures interact to shape human experiences and societal organization.

- Interest in Norms, Values, and Beliefs: Anthropologists and sociologists are deeply invested in studying norms (socially accepted behaviors), values (what a society considers important), and beliefs (shared views about the world). They view these social constructs as dynamic and adaptable, changing over time, across different cultures, and in various contexts. By examining these shifts, both disciplines aim to understand how societies function and evolve.

- Consideration of Individual and Collective Behaviors: Both anthropology and sociology provide valuable insights into individual behaviors and collective actions within societies. They seek to explore the intricate relationships between personal choices and social contexts, examining the range from individual micro-level behaviors to the actions of larger social groups. This dual focus helps illuminate how individual decisions are influenced by and, in turn, shape broader societal dynamics.

- Interdisciplinary Research: Sociology and anthropology often work alongside other disciplines to explore complex social phenomena from various viewpoints. This interdisciplinary approach enables a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of human society and culture.

The relationship between sociology and anthropology is marked by both notable similarities and distinct differences. Both disciplines share a mutual interest in exploring human society, culture, and behavior, but they approach these topics from different perspectives and employ unique methodologies.

By appreciating the unique contributions of each discipline, along with their areas of overlap and collaboration, we can develop a richer and more nuanced understanding of the complexities of human social life.

The ongoing dialogue and exchange between sociology and anthropology are likely to provide valuable insights into the nature of human society and culture, enhancing our comprehension of contemporary social issues and the wider human experience.

Previous Year Questions

- Discuss the nature of Sociology. Highlight its relationship with Social Anthropology (2024)

Important Keywords

Wright Mills, Study of humanity, Archaeology, Physical anthropology, Cultural anthropology, Linguistic anthropology, Social anthropology, Indian, Sudanese, Naga, Santhal, Social Organization, Sociological Social Psychology, Social Change, and Criminology, Qualitative and Quantitative Methods, Norms, Values, and Beliefs and Interdisciplinary Research.

Sociology and History

Sociology

Sociology is a social science that studies human societies, their interactions, and the processes that preserve and change them. It does this by examining the dynamics of constituent parts of societies such as institutions, communities, populations, and gender, racial, or age groups.

Sociology also studies social status or stratification, social movements, and social change, as well as societal disorder in the form of crime, deviance, and revolution.

History

History is a narration of the events which have happened among mankind, including an account of the rise and fall of nations, as well as of other great changes which have affected the political and social condition of the human race.

According to Radcliff Brown “sociology is nomothetic, while history is idiographic”.

In other words, sociologists produce generalizations while historians describe unique events.

An example for this claim are R.H. Tawny’s work “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”, Weber’s thesis “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism”.

“The Polish Peasant” by Thomas and Znaniecki consist of mere description of a peasant family, and therefore, is idiographic as any historical study can be.

Goldthorpe argues that history and sociology are two significantly different intellectual enterprises. He concludes that it is wrong to conclude to consider sociology and history as one. History in no sense is a natural science like sociology. It does not seek colourless units. It is said that history interprets whereas natural science explains.

Differences between Sociology and History

|

Sociology

|

History

|

|---|---|

|

Sociology is a social science that studies human societies, their interactions, and the processes that preserve and change them. |

History is a narration of the events which have happened among mankind, including an account of the rise and fall of nations, as well as of other great changes which have affected the political and social condition of the human race. |

|

Sociology is interested in studying the present social phenomenon. |

History is interested in studying the past phenomenon. |

|

Sociology is an analytical science.

|

History is a descriptive science.

|

|

Sociology is abstract in nature

|

History is concrete in nature.

|

|

Sociology is generalising science.

|

History is individualising science.

|

|

Sociologists believe their understanding transcends space-time dimension. |

Historians emphasise their findings as time–space localised. |

Interrelations between Sociology and History

- Sociologists often refer to history to explain social changes, developments and changing face of society over period of time. Similarly, history also needs social aspects (sociological concepts) to explain past.

- Social change is a reality. It has to happen. History shows mirror or truer way to analyse it with respect to time and space. History, in fact, said to be the constant reminder of the fact that change, even though permanent, is irregular and unpredictable.

- History thus provides a frame of reference and contextual tool to examine and analyse change carefully.

- Both sociology and history thus depend on each other to take complete stoke of reality.

- Sociology is also concerned with the study of historical developments of society. Sociologist studies ancients or old traditions, culture, growth of civilisations, groups and institutions through historical analysis and interpretations.

- The development of sociological theories is traced in 19th and 20th century historical developments at the level of philosophy, epistemology and progressive thinking.

- Specifically, sociological theories have been product of intellectual, social, cultural and political climate within which they were developed. For instance, enlightenment was a period of remarkable intellectual development

Historical sociology

- Historical sociology is a branch or sub-discipline of sociology. It emerged, during the twentieth century, primarily as a result of intersection between sociology and history.

- Historical sociology as a sub-field of sociology is likely to make two major contributions to the discipline.

- Firstly, it can fruitfully historicise sociological analysis helping to situate any sociological analysis historically.

- Secondly, it will help to draw on important social issues which critically required historical analysis but somehow avoided or remain neglected in sociological analysis.

- Sociologists often talk of the, ‘context’, while studying or explaining society in terms of its structure, functions and changes.

- Here, time and space are two important factors which inherit and explain the contextual aspects of social reality. Time is crucial factors in explaining the evolution of social reality as social realities get shaped over period of time.

- Since, history take care of factors such as time or periodical evolution of societies, it essentially helps sociologist to study society in much more systematic fashion.

- It helps sociologists in providing rationale to articulate present status and developmental trajectory of a society.

- Various sociologists such as Comte in his law of three stages, Spencer in his analysis of evolution of societies, Weber in his elaboration of ideal types and growth of city, and Marx in his analysis of class conflict and social changes, have used historical dimension in their sociological analysis.

- Hence, history and sociology are closely related to each other. However, we may also note that both the disciplines differ in their nature and approaches, nevertheless intersect or criss-cross each other on many points.

- Resultantly, historical sociology emerged as an off- shoot such intersection between the two disciplines.

Historical sociology as an outcome of intersection of the both the disciplines have emerged. It is also described that the historical sociology as branch of sociology has critically contributed to the growth of an interdisciplinary scholarship. Many sociologists, from the beginning of sociology as major discipline, such as Marx, Weber, Durkheim, later on Castells, Amin, Frank, Blaut as discussed, have elaborately contributed in this field. In nutshell, both sociology and history, though being two different disciplines in the domain

of social sciences, are very much closely interrelated and supplements each other’s field of studies.

Previous Year Questions

- Discuss the relevance of historical method in the study of society (2015)

Important Keywords

History, Sociology, Institutions, Communities, Populations, Gender, Racial, Age groups, Radcliff Brown, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Thomas, Znaniecki, Goldthorpe, Analytical and Descriptive science, Concrete, Abstract, time–space and Historical sociology.

Sociology and Psychology

Sociology

The term sociology was coined by Auguste Comte, who is called the father of Sociology. Sociology is concerned with the study of human relationships and the society. It is believed that relationships develop when individuals come in close contact with other and interaction takes place between them. This leads to the formation of social groups and complex relationships among these groups develop as result of constant interaction.

Hence, it can be said that social self and individual self are two parts of the same coin. Given this, scholars have attempted to define and explain the subject matter of sociology. One of the founding fathers of sociology, Auguste Comte divided the subject matter of sociology into the study of social static and social dynamic.

The static was concerned with the study of how the parts of the societies inter-relate, the dynamic was to focus on whole societies as the unit of analysis and to show how they developed and changed through time.

According to Emile Durkheim sociology is the study of social facts. Sociology can be defined as the scientific study of human life, social relations, social groups and every aspect of the society as a whole. The scope of sociology is very wide, ranging from the analysis of the everyday interaction between individuals on the street to the investigation and comparison of societies across the globe.

Psychology

The term psychology is derived from two Greek words; Psyche means “soul or breath” and Logos means “knowledge or study” (study or investigation of something).

Psychology developed as an independent academic discipline in 1879, when a German Professor named Wilhelm Wundt established the first laboratory for psychology at the University of Leipzig in Germany. Initially, psychology was defined as ‘science of consciousness’.

In the simple words, we can define psychology as the systematic study of human behavior and experience. According to Baron (1990), psychology is the science of behaviour and cognitive processes. Psychology emphasizes on the process that occurs inside the individual’s mind such as perception, cognition, emotion, and consequence of these process on the social environment.

Thinker’s view

- S. Mill: Argued for the primacy of psychology over other social sciences, believing that all social laws are derived from the laws of the mind.

- Sigmund Freud: Suggested that sociology is essentially an extension of social psychology, linking societal behavior to psychological principles.

- Émile Durkheim: Made a clear distinction between sociology and psychology, viewing them as studying different types of phenomena.

- Ginsberg: Claimed that many social structures and organizations could be better understood by relating them to general psychological laws.

- Max Weber: Believed that sociological explanations are enriched by understanding social behavior in terms of the underlying meanings individuals assign to their actions.

Differences between Sociology and Psychology

|

Sociology

|

Psychology

|

|---|---|

|

Sociology is the study of individual as well as of society. |

Psychology is the study of personality. |

|

Subject matter of sociology includes family, individual, power, etc. |

Subject matter of psychology includes sympathy, imitations and passions. |

|

Sociology is a general study of society and has a wider scope. |

The scope of psychology is limited and focused on man’s mental activities. |

|

The view that sociology is a science is often debated. |

Psychology has more scope of experimentation. |

|

Sociology helps one to see the world through the prism of different communities and cultures. |

Psychology helps one to see the world through the lens of different individuals having different behaviours. |

|

Sociology can help a person build a career in human resources, social research and justice related analysis. |

Learning psychology can help building a career in criminal justice, public administration and social services, forensics, clinical psychology, marriage counselling, solving problems associated with addiction and substance abuse etc. |

Link between Sociology and Psychology

Sociology and psychology together form the core of the social sciences. Right from their inception as separate academic disciplines, sociology and psychology have studied different aspects of human life.

Most of the other species, work on instincts in the physical environment for their survival. While the survival of humans depends upon the learned behaviour patterns. An instinct involves a genetically programmed directive which informs behaviour in a particular way. It also involves specific instruction to perform a particular action (Haralambos and Holborn, 2008).

For instance, birds have instincts to build nests and members of particular species are programmed to build a nest in a particular style and pattern. Unlike this, the human mind is influenced by the social culture, customs, norms, and values. It through socialization that humans learn specific behaviour patterns to suit them best in the physical environment. Humans process the information provided by the social context to make sense of their living conditions. Sociology’s basic unit of analysis is the social system such as family, social groups, cultures etc.

The main subject matter of psychology is to study human mind to analyses attitude, behaviour emotions, perceptions and values which lead to the formation of individual personality living in the social environment.

While sociology deals with the study of the social environment, social collectives which include family, communities and other social institutions psychology deals with the individual.

For instance, while studying group dynamism, sociologist and psychologist initially share common interest in various types of groups, and their structures which are affected by the degree of cooperation, cohesion, conflict, information flow, the power of decision making and status hierarchies. This initial similarity of interest, takes on different focus, both the disciplines use different theoretical positions to explain the group phenomena.

Social Psychology

There is constant interaction between the intra-individual and social context and both influence each other mutually.

Social psychology could be defined as the study of the “interface between these two sets of phenomena, the nature and cause of human social behaviour”.

G.W Allport defines social psychology with its emphasis on “the thought, feeling, and behaviour of individual as shaped by actual, imagined, or implied the presence of others”.

A few other definitions of social psychology are as follows: Social Psychology is the discipline that explores in an in-depth manner the various aspects of social interaction.

Baron and Byrne (2007) define social psychology as the scientific field that seeks to understand the nature and causes of individual behavior in social situations.

To sum up we can say that social psychology is the systematic study of people’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviour in the social context.

Inter-disciplinary Approach to Social Psychology

The definition given by Allport suggests that the roots of social psychology are embedded in sociology as well as psychology.

Scholars such as Cook, Fine, and House (1995), Delamater (2006) are of the view that social psychology essentially includes analysis and synthesis of major works in the field of sociology and psychology hence, it is interdisciplinary in nature.

The main subject matter of social psychology is the study of the individual in the social context. In other words, the mind, self and society are the subject matters of social psychology.

There are many sociological and psychological perspectives used in social psychology to explain and understand the constant influence of human and society on each other.

Depending upon the approach, purpose, and focus of the study social psychology could be is further divided into sociological social psychology and psychological social psychology.

It is very difficult to make clear distinctions between the two, as social psychology tends to draw from both the disciplines of sociology and psychology.

The cognitive social psychology or the social cognition is an approach that investigates how information is processed and stored.

According to Thoits “information is stored as prototypes, schemas, and the like; information processing includes attending to cues, retrieving from memory, and making judgments, inferences and predictions about oneself and others.”

In this approach, cognition is seen as social because it originates from the social experience and bears consequence on the interpersonal behaviour. Sociological social psychology concentrates on the mass psyche, the psychology of classes and the elements of group mentality such as customs, moral and traditions. In other words, it focuses on small group dynamics.

Important Keywords

History, Sociology, Institutions, Communities, Populations, Gender, Racial, Age groups, Radcliff Brown, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Thomas, Znaniecki, Goldthorpe, Analytical and Descriptive science, Concrete, Abstract, time–space and Historical sociology.

Sociology and Economy

Sociology

Sociology focuses of organization of social relationships and attempts to analyse the dynamics of organized patterns of social relations and social behaviour. One can say that primarily it tries to answer three basic questions.

Firstly, how and why societies emerge?

Secondly how and why societies persist?

And how and why societies change?

Most of the sociologists agree on the following

- The major concern of sociology is with the analysis of human social behaviour and relationships.

- Sociology gives attention to the study of primary social institutions such as family and maintenance of social order.

- Sociology focuses on evolution, transformation and functioning of social life.

- Sociology deals with social process such as co-operation and competition, accommodation and assimilation, social conflict, communication in society, social differentiation and social stratification.

Sociology has its own methodology and is based on empirical data collection and inductive reasoning but also has deductive aspects at the level of generalizations.

Economics

Economics is a social science that deals with human wants and their satisfaction. Classical economics assumes that people have unlimited wants and the resources to satisfy these wants are limited. They are always engaged in work to secure the things they need for the satisfaction of their wants.

The farmer in the field, the worker in the factory, the clerk in the office, and the teacher in the school are all at work.

The basic question that arises here is:

Why different people undertake these activities?

The answer is that they are working to earn income with which they satisfy their wants. People have multiple wants to satisfy. People’s multiple wants include basic needs such as food, cloth, shelter and other needs like better education, better health facilities etc.

According to one perspective it is assumed that there is no limit for human wants, it is insatiable. When one wants get satisfied, another want automatically takes place and so on in an endless succession. Hence, we say that it is impossible to satisfy one’s wanted.

People earn money by doing some work or activity and they use this money to satisfy their wants.

Economics is about the conversion of raw material into usable good, called production. The use of these goods called consumption and the distribution of resources in society.

Thus, human activities have two common aspects; first, we are all engaged in providing for our needs, and secondly, needs vary for different goods and services. This action of acquiring resources and spending is called economic activity.

Seligman says, the starting point of all economic activity is the existence of human wants. Wants give rise to efforts and efforts secure satisfaction. The things which directly satisfy human wants are called consumption goods.

A few consumption goods like air, sunshine, etc. are abundant. They are available at free cost. But most of goods are scarce. They are available only by paying a price.

And, therefore, they are called economic goods. They do not exist in sufficient quantity to satisfy all wants.

Thinker’s view

- Robbins: “Economics is a social science which studies human behaviour in relation to his unlimited ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.” It largely focuses on the activities of man such as production, consumption, distribution and exchange. It also studies the structure and functions of different economic organizations like banks, markets etc.

- C. Pigou: “Economics studies that part of social welfare which can be brought directly or indirectly into relationship with the measuring rod of money.”

- John Stuart Mill: He defines the subject of economics as “The science which traces the laws of such of the phenomena of society as arise from the combined operations of mankind for the production of wealth, in so far as those phenomena are not modified by the pursuit of any other object.”

- Alfred Marshall: “Economics is the study of mankind in the ordinary business of life; it examines that part of individual and social action which is most closely connected with the use and attainment of material requisites of well-being.”

- Max Weber: He defines sociology as “The science which attempts the interpretative understanding of social action in order thereby to arrive at a causal explanation of its cause and effects.”

- Morris Ginsberg: “In the broadest sense, sociology is the study of human interactions and inter-relations, their conditions and consequences”.

Differences between Sociology and Economics

|

Sociology

|

Economics

|

|---|---|

|

Sociology primarily studies about society and social relationships. |

Economics studies about wealth and choice. |

|

Sociology emerged as a science of society very recently. |

Economics is comparatively an older science. |

|

Sociology is considered as an abstract science. |

Economics is considered as a concrete science in the domain of social sciences. |

|

Sociology generally deals with all aspects of social science. |

Economics deals specific aspects of social science. |

|

Sociology has a very wide scope.

|

Economics scope is very limited.

|

|

Sociology is concerned with the social activities of individuals. |

Economics is concerned with their economic activities. |

|

Society is studied as a unit of study in Sociology. |

Individual is taken as a unit of study in economics. |

Similarities between Sociology and Economics

- Both Sociology and Economics are branches of social science that focus on the study of human development and behaviour.

- Both disciplines use scientific methods to investigate and analyse their respective fields.

- Economics and Sociology are interdependent; while Economics focuses on the economic aspects of human life, it is inherently linked to social activities.

- Likewise, Sociology, which studies social beings, is significantly influenced by economic factors.

- Economics is regarded as a branch of social science, and historically, it has been considered a sub-discipline of Sociology.

Economic Sociology

According to Britannica encyclopaedia, economic sociology is the application of sociological methods to understand the production, distribution, exchange, and consumption of goods and services.

Economic sociology is particularly attentive to the relationships between economic activity, the rest of society, and changes in the institutions that contextualize and condition economic activity.

One can see the roots of economic sociology in the classical philosophical and social science tradition; however, it emerged as a systematic academic subdivision of sociology in less than a century ago.

After it became an academic sub discipline of its parent discipline, it has made remarkable contribution in analysing society from an economic perspective.

If we closely observe, we can find out that the birth of economic sociology in the writings of Karl Marx.

Smelser, N.J and Swedberg. R says that the first use of the term economic sociology seems to have been in 1879, when it appears in a work by British economist W. Stanley Jevons ([1879] 1965).

The term was taken over by the sociologists and appears, for example, in the works of Durkheim and Weber during the years 1890–1920.

It is also during these decades that classical economic sociology is born, as exemplified by such works as The Division of Labor in Society (1893) by Durkheim, The Philosophy of Money (1900) by Simmel, and Economy and Society (produced 1908-20) by Weber.

These classics of economic sociology are remarkable for the following characteristics.

First, Weber and others shared the sense that they were pioneers, building up a type of analysis that had not existed before.

Second, they focused on the most fundamental questions of the field: What is the role of the economy in society? How does the sociological analysis of the economy differ from that of the economists? What is an economic action? To this should be added that the classical figures were preoccupied with understanding capitalism and its impact on society — “the great transformation” that it had brought about.

Contemporary Economic Sociology

In the recent times, especially after 1980’s, economic sociology experienced a remarkable revival. Few sociologists, who were doing rigorous research on the relationship between market and society, contributed a flurry of articles on the networks of market and society, which eventually lead to the revival of economic sociology into an important subfield of sociology.

The main contributor of 1980’s was Mark Granovetter, who emphasized on the embeddedness of economic action in concrete social relations.

In the article Economic Institutions as social constructions, Granovetter argues that institutions are actually congealed social networks, and, because economic action mostly takes place in these networks, social scientists must consider interpersonal relationships while studying economy.

He further argues that in the contemporary economic sociology markets are considered as networks of producers watching each other and trying carve out niches.

Hence, we can say that such networks are the core area of concern in the contemporary economic sociology.

Karl Polanyi is another renowned contributor to economic sociology, argued that the birth of the free market was an institutional transformation necessarily promoted by the state. This got a general acceptance in the domain of economic sociology.

Origin of New Economic Sociology

Convert. B and Heilbron. J in their article ‘Where Did the New Economic Sociology Come From’ provides a detailed account of the emergence of new economic sociology.

They argue that the new economic sociology obtained its scientific legitimacy by bringing together two promising new currents: network analysis and neo-institutionalism, along with a more marginal cultural mode of analysis. This has led to the “new economic sociology,” to become one of the liveliest subfields of sociology.

Important Keywords

Sociology, Economics, Social Process, Classical economics, Production, A.C. Pigou, John Stuart Mill, Alfred Marshall, Morris Ginsberg, Economic sociology, Division of Labor in Society, The Philosophy of Money, Economy and Society, Contemporary Economic Sociology, Mark Granovetter, Karl Polanyi and New Economic Sociology.

Sociology and Political Science

Sociology

Sociology is devoted to the study of all aspects of society. Sociology stresses the interrelationships between sets of institutions including government.

Sociologists like Max Weber worked in what can be termed as political sociology. The focus of political sociology has been increasingly on the actual study of political behavior.

Even in the recent Indian elections, one has seen the extensive study of political patterns of voting. Studies have also been conducted in membership of political organizations, process of decision-making in organizations, sociological reasons for support of political parties, the role of gender in politics, etc.

According to Marx, political institutions and behavior are closely linked with the economic system and social classes.

Political science

Political science is generally defined as a scientific study of state, government and politics. The concept of politics is central to political science. In fact, sometimes both are used interchangeably.

In general, politics is also defined as a process whereby people form, preserve and modify general rules which govern their lives. Such processes generally involve both cooperation and conflict.

Politics as an art of governance is thus engaged with the issues of public affair, conflict, multiple decisions making, compromises and consensus at different levels and, thus, essentially delineating concerns related to power and distribution of resources.

Now, let us look at some of the meanings attached to the word politics:

Firstly, politics is often considered as an art of government. The word politics is derived from the word, ‘polis’ which literally means, ‘the city state’. In this context, politics or political science is often referred to affairs of polis- means the concerns or the matters related to state and its affairs. Political science as an academic discipline has largely adopted this definition of politics or political science.

Secondly, Politics primarily deals with public affairs, but its scope extends beyond just the study of government or state. It involves both public institutions like the police, army, and courts, which serve society as a whole, and private institutions like families and businesses, which focus on individual needs and interests.

Thirdly, Politics is often defined by its focus on compromise, decision-making, and consensus. It deals with resolving conflicts through negotiation, dialogue, and arbitration, rather than relying solely on force. Scholars call politics “the art of the possible” because it aims to find peaceful solutions. Politics also involves the distribution of power and resources to ensure a smoothly functioning society.

Lastly, Politics is often linked to power and influence. Scholars see it as central to all social activities, both formal and informal, at various levels—family, groups, organizations, and global society. Politics revolves around power, the ability to influence others, and the struggle for limited resources. Political science studies this power, governance, and state structure. Like sociology, political science seeks to impart knowledge, not practical political training. Over time, political science has adopted an interdisciplinary approach, borrowing from fields like sociology, broadening its scope and methods. Understanding this shift helps in appreciating the connection between sociology and political science.

Thinker’s view

- Lipset: It is said that the disciplines of sociology and political science are closely interwoven in their analysis of power, authority structures, administration and governance.

- According to Jain and Doshi (1974), when vocabulary of political science is translated into the vocabulary of sociological analysis it is then what we call political sociology.

Similarities Between Sociology with Political Science

Firstly, political science relies heavily upon sociology for its basic theories and methods. For example, in mid-20th century Michigen social psychologists and Parsonians at Harward significantly shaped political science agendas in political behaviour and political development respectively.

Secondly, focal specialities in both the discipline borrowed from similar third-party disciplines such as economics, history, anthropology and psychology.